The story behind 19th century Chinese migration

China's two south-eastern provinces of Guangdong and Fujian have been international trade hubs since at least the 10th century. Facing the South China Sea and the Pacific, these two provinces are closer to South-East Asia than they are to Beijing, the modern Chinese capital.

For the majority of China’s history, up to the end of WWII, almost all migrants came from Guangdong and Fujian. The thing that attracted them was trade, particularly with close neighbours like Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, Indonesia, Cambodia and Thailand.

Between 1405 and 1433 the renowned admiral Zheng He was sent on seven great voyages to flaunt the power of the Ming Empire to tributary states and neighbours. The voyages were also part of the Yongle emperor’s attempts to reinforce the shaky grounds to his claim to the Ming throne, having deposed the legitimate emperor in 1402. While the size of the fleets was unprecedented – around 300 ships – the routes they took were not. The ships followed the trade route between China and the Arabian Peninsula known as the Maritime Silk Road. This had been used since at least 2 BCE. In the early 1400s when Zheng He’s fleet arrived at Malacca (now in Malaysia), there was already a sizable Chinese community, as there was in almost every other country the fleet visited.

Zheng He’s voyages dramatically increased trade and the movement of people between Guangdong, Fujian and the nations of the south-east Asian region, making these two provinces China's wealthiest and most developed. Greater levels of trade also fostered the already strong spirit of independence and openness to outside ideas. This open attitude remained, even when different Chinese administrations took a more isolationist approach. Between 1757-1842 the Manchu rulers of the Qing dynasty sought to restrict foreign trade by making Guangzhou (Canton) the only port in China through which foreigners were able to trade. Despite the many and irksome restrictions imposed on the Western traders, trade continued - although not at the level that Britain and other foreign powers would have liked.

In 1839 Britain instigated military action to forcibly open Chinese ports to free trade - the First Opium War. After China's defeat in 1842 Britain forced open five southern ports: Guangzhou, Xiamen, Fuzhou, Ningbo and Shanghai. This was done under the Treaty of Nanking. Other foreign powers soon demanded the same trading rights as Britain, and international trade rose dramatically in volume. For China, the defeat unleashed devastating social and political upheaval. Arguably, the effects of this are still being felt today.

However, even before the First Opium War, the ruling Qing Dynasty was already on shaky ground. A population explosion in China that started in the late 17th century had doubled the population. Ironically this was partly caused by the introduction of new foods from the Americas, such as potatoes, which were brought in by international traders in Guangzhou. The inevitable results were fewer resources, increased taxes, inflation, lawlessness, government corruption and civil unrest. War[1] and foreign pressures accelerated this breakdown in civil society.

This upheaval was one of the reasons for a substantial increase in migration from Fujian to Southeast Asia from 1842, and from Canton and Hong Kong to the white Pacific nations from 1848. The other big reason for migration was the great and expanding wealth of the British Empire and other Western nations.

A particular drawcard was the discovery of gold in all four white Pacific nations between the 1840s and the 1860s, and a perception that they were all socially and economically stable. What also attracted migrants was trade-friendly governments - they could trade without legal restrictions - and a justice system that for Chinese and other settler colonisers was largely unbiased. Of course, this was not true for the colonised and indigenous populations. But for Chinese migrants, these conditions meant that earning a good and steady living was perfectly possible.

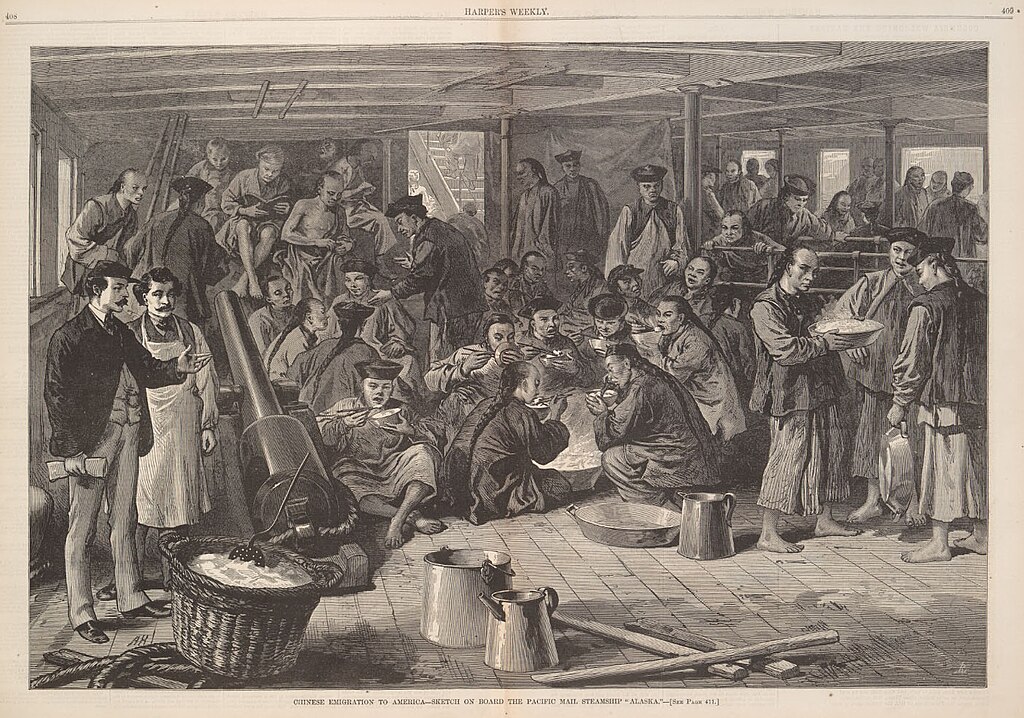

The last main reason for the increase in migration was the invention of steamships. Steamships dramatically reduced the cost of travel while increasing safety and comfort. Previously, sailings from China to Pacific ports tended to be quite haphazard as they were largely based on demand and seasonal weather conditions. There were some times of the year when you couldn't sail. With the rise of steamships and shipping companies, the number of sailings increased and passengers were able to rely on regular schedules and reliable passages between the ports.

For Chinese migrants travelling from Hong Kong to New Zealand, steam meant a much faster journey. By sail a voyage could take up to three months: by steam it took three weeks. An additional factor was the rapid development of colonial Hong Kong which became a major shipping and commercial hub - with all of the associated colonial infrastructure. As a centre of global exchange, it facilitated business ties across the overseas Chinese diaspora. It has been said that Cantonese migration made Hong Kong possible, while Hong Kong made Cantonese migration possible.

By the late 1930s there were around 8.7 million overseas Chinese, just over 90% living in Southeast Asia. New Zealand was the country with the second lowest Chinese population at 2,367, less than 1% of the total number of Chinese migrants in the period from 1848 to 1948. Fiji had the smallest number of Chinese at 1,751.[2]

However, population figures of the 1930s tell only part of the story. In New Zealand, Statistics New Zealand figures record 22,836 Chinese arrivals between 1872 and 1941.[3] These include temporary visitors and Chinese returning to New Zealand. Over the same period, the number of departures was 19,825, reflecting high levels of mobility and traffic between the two countries. Not surprisingly, the period with the largest numbers of arrivals was the gold seeking period pre-1881 and before the New Zealand Government introduced restrictions on Chinese migrants.