Ho A Mei: the man who brokered New Zealand's first Chinese goldminers

Chinese miners were a significant part of the Otago and West Coast goldfields. But they may not have come if it were not for the efforts of Melbourne businessman, Ho A Mei (何亞美) who is credited with bringing the first Chinese miners to Otago in 1865.

Otago’s economic balloon burst in 1864, just as the goldminers had cleaned out most of the easy pickings. The effect on Dunedin was swift: ‘Business during the last three weeks has been worse than ever, a thing which, three weeks ago, few believed possible . . . . In all directions "To Let" is to be seen in stores, offices, shops, and houses, and the value of city property cannot be certainly estimated from one week to another.’[1]

It was in this climate that the Dunedin Chamber of Commerce decided to invite Chinese miners from the Victorian goldfields to revive Otago’s economy.[2] Their initial approach in 1865 was likely made to Lowe Kong Meng, an extraordinary Chinese Australian who was both a community advocate and one of the founding directors of the Commercial Bank of Australia, now part of Westpac.[3]

However, when presented with the invitation the Chinese mining community was not enthusiastic. The immediate concern was safety. In Australia, Chinese miners had been attacked and three were killed in the Buckland Riot in 1857. New Zealand miners seemed just as hostile. In 1863 the Southland Times published this sinister paragraph:

. . . John Chinaman will not find himself so much 'at home' in this part of the world as in Victoria or New South Wales. Some of the friends of these interesting bipeds should warn them of the risk they run in rushing to the New Zealand diggings, as the banks of the rivers here are much steeper, and the current much stronger, than that of the Buckland.[4]

It is understandable that despite an explicit invitation, Victoria’s Chinese wanted a formal assurance from Dunedin that their lives and property would be protected by law just like those of the Europeans. This was probably more about making a political point, than it was about expecting any extra protections. In any case, the request was publicly noted and duly passed to a higher governing body: the Otago Provincial Council.[5][6]

In turn, the Provincial Secretary, F Walker, wrote as follows:

. . . that this Government recognise no difference between Chinese and any other class of immigrants, and will of course extend to them the same protection, both in respect to property and person, as is already afforded to all other inhabitants of the Province.[7]

It was this letter that was sent to the 'leading Chinese merchant in Melbourne'[8] - Lowe Kong Meng. In turn, Lowe passed the matter over to Ho A Mei, a bright young interpreter and businessman who was chosen to visit Dunedin as the community’s envoy.

Born in the Nam Hoi (Nanhai) county of Guangdong around 1838, Ho was an orphan who had been sent to the London Missionary Society’s Ying Wa College in Hong Kong. With his English education and being able to speak several Cantonese dialects, Ho became an interpreter on a warship in his late teens. In 1858, he joined his brother Ho A Lo who was a preacher and interpreter on the goldfields of Victoria.

Ho A Mei was quick to establish himself in Melbourne. By 1864 he had married a young Englishwoman called Sarah Foster, started a family, become naturalised and had invested, somewhat unsuccessfully, in mining ventures.[9] In taking up the Dunedin project, his gamble was that hundreds of Chinese Australian miners would soon be flocking to New Zealand. This would put him in the prime position for supplying all of them with goods and services.

However, first of all he had to check the terms of the invitation and make arrangements for future miners. His first concern was safety.

Expressions of threats against Chinese lives, should they tread upon the soil, had been freely used by the European diggers. Hence, it was for due protection of Chinese generally that I first set foot upon the shores of Dunedin.[10]

Ho understood the depth of miners’ violence and the importance of redress. His brother A Lo had been the Police interpreter in the aftermath of the 1857 Buckland riot. Although 11 of the ringleaders had been arrested, juries found them guilty on only three minor charges, despite the deaths of three Chinese.[11] This was widely viewed as a travesty of justice at the time.

Despite these fears, Ho’s later account of the venture shows his unbridled enthusiasm for the Otago project.

Some time in the month of November [Dec] 1865, being an energetic and enterprising man, blessed with the health and the hopefulness of youth, and more especially animated by a spirit of speculation, I started from Melbourne [and] arrived at your beautiful and picturesque city [Dunedin] accordingly. . . . [Being] not a miner myself, my view therefore was to first secure the introduction of labour; then, with a hope to reap the benefit by having the full command of provisioning business, should the scheme be proved successful.[12]

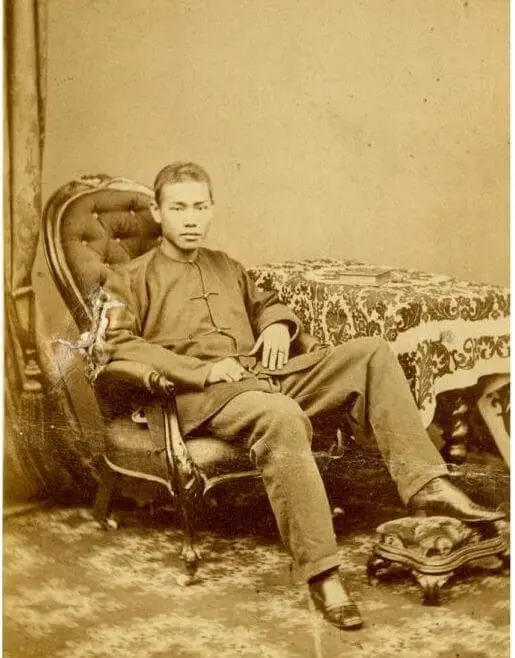

It is not known what the people in Otago were expecting when Ho A Mei arrived in the South Australian on 12 Dec 1865. Cartoons published in the Dunedin Punch portrayed him as a pantomime figure: a stout man in oriental robes, with a dangling moustache and two long braids. But this could not be further from the reality.

Ho arrived as a well-dressed, self-assured young man, with a gold chain on his waistcoat and a natty walking stick. ‘Indeed he is quite a swell, walks our principal streets, smokes his Cheroot, shakes hands with our best merchants and talks English as well, or nearly so, as any born native,’ wrote a surprised Dunedin observer.[13]

Ho’s time in Dunedin was well spent in the company of William Tolmie, James Rattray and others from the Chamber of Commerce. He consulted an influential miners’ agent, Duncan Campbell, while the Otago Provincial Council provided him with a letter of introduction for prospective Chinese miners to carry with them.[14] At leisure, he went to the theatre and dined under the ‘hospitable roofs’ of his Dunedin hosts. Interestingly, all the men he met originally came from Victoria. As an entrepreneur, Ho A Mei found kindred spirits in Dunedin.[15]

Back in Melbourne, the Chinese response to Ho’s Dunedin visit was less than encouraging. Miners doubted the opportunity and ‘feared to risk what little they possessed’. Ho was obliged to dig into his own pockets. For several months he was lending each new miner £20 for travel costs and equipment.[16] In the end, the first scouting party of five men arrived in Port Chalmers on 23 December 1865.[17] They set out up the Pigroot for Blackstone Hill, the site of Otago’s most recent rush. Eight reinforcements joined them in January 1866.[18]

According to the Otago Daily Times: ‘The party hired a dray in the forenoon, got it loaded with their swags, and provisions which they brought with them, and a start was made early in the afternoon.’[19] Their provisions included 40 bags of rice, 2 cases of Chinese oil and a bag of salt fish which Ho A Mei had sent with them.[20]

Ho returned to Otago in February 1866, travelling saloon, with two dozen Chinese miners as steerage passengers. A dozen Seyip men went north to Blackstone Hill, while the other twelve Sam Yup men set out for the Tuapeka district. After an overnight camp at Waitahuna, they entered the settlement which would soon be the town of Lawrence, guided to potential mining sites by Duncan Campbell, the local mining agent.

Rumours soon spread that 3,000 Chinese were expected on the Otago goldfields.[21] These were probably sparked by Ho A Mei’s enthusiasm. Anticipating these large numbers, Ho hired lodgings and two Chinese cooks to host newcomers. However, few miners came in the following months. It took a year before Otago’s Chinese population reached 1,000, and another five before it hit the 3,000 mark.

Ho A Mei grew tired of waiting for his investment to mature and returned to China. He later estimated that he spent £800 on his Otago venture (worth over NZ$90,000 in 2023),[22] calculating that he got back less than half. However, he wasn’t quite finished with New Zealand. During 1871 he helped charter nine ships that took 2,084 men from Hong Kong direct to Otago.

Fortunately, Ho A Mei won out in the long run. Returning to China, he applied what he had learned about business in Australia and New Zealand. He made a fortune investing in insurance, the telegraph and silver mining. His biographer, Dr Elizabeth Sinn, wrote, ‘Armed with mining knowledge from Australia, he transformed the mining scene in South China.’

He also used his wealth and experience with the Otago Chamber of Commerce to help set up a Chinese Chamber of Commerce in Hong Kong and was its first President. He is remembered today as a notable activist, defending the interests of Chinese in the then British colony of Hong Kong.